Position of Health in the EU Enlargement Negotiations and Neighbourhood Policy

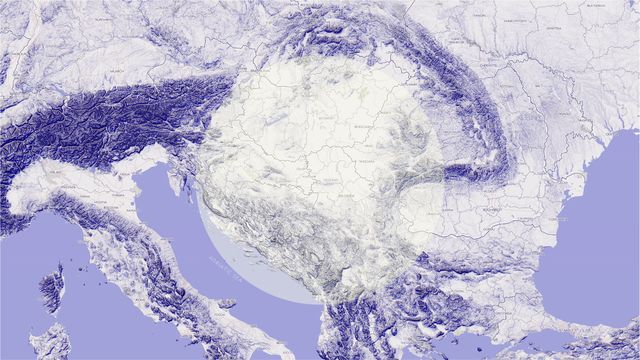

The integration of Western Balkans has been long promised by the European Union. It has, however, recently shown a rather reluctant position towards another enlargement. At the same time, we assist to a certain “promise fatigue” in the Western Balkans, where the EU transformative power to incite reform via the conditionality of acquis communautaire, is fading alongside with its popularity in the region. This article argues, why the Health sector represents one of the key areas for the EU to invest in. It focuses on mutual problems and challenges brought by accession in the area of Human Health and it calls for more political action, finance as well as academic studies on the topic.

The insufficient action of the EU on Human Health has been linked to an unclear legal framework and competence division, which are projecting into its external action. Technically, the EU has a limited legislative power in Human Health, however, its role as a policymaking authority is growing, as well as its overall involvement in the domain. As in other areas, it finds itself between necessity to regulate common human health issues, and an obligation to stay out of competencies of the States. This situation is then projecting into the accession negotiations.

Necessity to prepare for challenges brought by accession

First, the (potential) candidate countries are required to align their policies with the European standards for Health as the EU aims to mitigate risks of including new countries with less developed health sector. However, they often lack resources and expertise necessary to fulfil the criteria, such as obligation to introduce the universal (or almost universal) health coverage, as well as to deal with challenges brought by accession. Apart from easier trafficking of illegal substances, the opening of market to alcohol and tobacco products may have negative consequences on society’s health. The acquis communautaire and the EU public health legislation should ensure that the accession means an opportunity to improve health instead of bringing new obstacles.

For example, the qualification of doctors is automatically recognized throughout the Union, it is imperative to ensure that the professionals from the candidate countries will be able to achieve the same levels of qualification. Moreover, the disparities of quality and budget among member states might lead to a significant brain drain phenomenon from the Eastern, and eventually South-Eastern countries, which makes them losers of accession in the domain of Health. In the case of post-accession Romania for instance, there has been a significant rise in migration of medical professionals to France, while the country has the lowest density of doctors in the EU. Worryingly, Albania, Bosnia & Herzegovina, and Kosovo, the possible candidate countries, and Montenegro as an actual candidate, have the lowest density of doctors on the continent. Therefore, their accession to the EU constitutes an opportunity but also a great danger if the systems don’t succeed to provide local opportunities for medical professionals.

Insufficiency of EU funding for Health projects

Hence, in order to help the candidate countries to achieve the required management level of health-related issues, they must be provided with an adequate support and assistance, specific for Health. Unfortunately, the EU still doesn’t allocate important funds and support to the health care sector among the IPA (pre-accession) and the ENI (Neighbourhood) beneficiaries. For instance, the 2019 Report of the EIB in the Western Balkans stated that: “Over the last decade, the EIB has expanded its lending into sectors such as healthcare and education.” The share of EIB funded projects in Health, however, remains very low, at 3.37%. The same neglect applies for the technical assistance and training given through TAIEX instrument and Twinning as well as for support of other local health (and mental health) supporting initiatives. Overall, the paradigms of Health cooperation are based on effect of Health improvement as a stimulation of economic development or mostly focused on security health issues such as preventing pandemics, especially in the Neighbourhood.

As the EU interest in common public health increases, there have recently been some relative improvements regarding funding for the ENP health projects, especially in the case of Ukraine and its successful cross-border cooperation with Romania, which was in fact oriented on Health. Also, the inclusion of Serbia, Moldova, and Bosnia & Herzegovina into the 3rd EU Health Programme for 2014-2020 has been a promising development. Whether this inclusion will continue depends on the efficiency of a new approach introduced by the Multiannual Financial Framework for 2021-2027, planning on creating one single instrument for social and youth policies.

Investing in Health to incite other acquis-driven reforms

It is, in fact, not only for health security and stability reasons that the EU should focus on health in the candidate and Neighbourhood countries. Certain academics and practitioners suggest that a new approach is necessary. Pierre Mirel, for instance, speaks of an economic and political double re-engagement enhancing investment in the Balkans, including Health sector. With its clear reluctance to another enlargement, what transformative power the EU now holds in the Balkans? The EU has been reluctant to intervene in the field of social and public policies, preferring the investment into other, mostly economic union-related areas, which are, however, much less evident for the local populations. Consequently, the policy-makers in the candidate countries started to neglect social policies because of the other requirements for accession, sometimes much more politically “painful” for them.

So, if the EU will not also include the support for local initiatives in the more “politically pressing” areas (social policies and health), won’t its transformative power and incentive to reform get increasingly fruitless? To maintain public support for accession in the candidate countries, its investment into these highly demanded sectors such as public health is necessary.

Finally, an investment in public health is equally an investment into self-sufficiency, sustainability and most importantly a more peaceful, healthy environment, an approach surprisingly not underlined in the EU approach towards Health. If the EU plans on cultivating its transformative power, in the candidate countries as well as in its neighbourhood, it should use its leverage to support policies that directly affect populations’ daily life. As Laaser, Donev, Bjegoviæ and Sarolli suggest in their article on Public Health and Peace: “‘Health and Peace’ should become a new discipline of health sciences.” Indeed, it ought to also become a new approach of health policies.