The American President Donald Trump and “The Worst” Deal

International law reflection of Miroslav Tůma, analyzing the Iran nuclear deal.

Introduction

Donald Trump, as the Republican presidential candidate in the 2016 pre-election talks, began to call the agreement dealing with the Iranian nuclear program from June 2015 “the worst" political deal ever. Since his election in November 2016, this pejorative labeling of the agreement with its various variations has continued and he does not conceal his interest in its cancellation. This is an important part of Trump's overall assertive strategy towards Iran, which coincides with a similar policy of two major US allies in the region, i.e. Israel and Saudi Arabia. In addition to his declared concern about the possibility of Iran obtaining nuclear weapons after the expiry of the agreement, it appears that the main cause of his position is the growing Iranian influence in the Middle East region, particularly in Syria, Iraq, and Lebanon, and Iran’s support of the Islamic movements Hezbollah and Hamas, which are marked as terrorist groups.

In May 2015, that is, a month before the agreement was negotiated, the Iranian Nuclear Agreement Review Act of 2015 (INARA) was approved by the Republican-led US Congress, and it required the President to periodically evaluate any agreement reached in the talks of the five permanent members of the UN Security Council, Germany and Iran to prevent the acquisition of nuclear weapons by the latter country. He was to give his opinion to Congress within a 90-day period enforced by law.

On the basis of the above law, President Trump granted the required certification of Iran's compliance with the deal twice in the first half of 2017, i.e. in April and July. However, by the October 13 deadline, he still did not provide the expected third certification, leaving Congress to decide within a 60-day period on the US's further steps in relation to the deal. By failing to certify it, President Trump has not withdrawn from the agreement and has also not called Congress to resume the anti-nuclear sanctions, which would most likely lead to an end of the agreement. However, according to Suzanne Maloney, the Deputy Director of the Foreign Policy Program at the Brookings Institution, "that step undermines the legitimacy of the agreement, which may lead to its collapse.

A brief characterization of the Iranian nuclear agreement and its main parameters

The Iranian nuclear agreement is officially called the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). In addition to Iran, the five permanent members of the UN Security Council (the PRC, France, the Russian Federation, the United States, and Great Britain) and Germany participated in the negotiations of the agreement, which were coordinated by the EU. It is a political agreement that does not have the character of a legally binding treaty and therefore does not require ratification by the participating states for its entry into force. However, according to the American lawyer Dan Joyner, some JCPOA commitments that have already been implemented by the parties, such as those that were adopted through the adoption of UNSC Resolution 2231 after the agreement had been reached, are legally binding. These include, for example, the Iranian temporary application of the IAEA Additional Protocol (until the ratification by Iran of this protocol), the removal of economic and other sanctions by the UN Security Council through the aforementioned resolution and the removal of unilateral sanctions on the basis of adjustments to national laws in the USA and the EU, which were implemented through the so-called implementation day of the JCPOA at the beginning of 2016.

The negotiation of the agreement, the content of which refers exclusively to the limitation of Iran's nuclear program in exchange for limiting UN, US and EU sanctions against Iran, has allowed for the satisfactory addressing of one of the most serious multi-annual security crises and a serious nuclear proliferation problem beyond the regional framework. The crisis was caused by the International Atomic Energy Agency’s (IAEA) suspicion that the Iranian party attempted to hide some parts of its nuclear program and its facilities from the inspectors of the organization. Despite repeated statements by the Iranian leadership about the peaceful nature of the nuclear program, including the announcement of two religious edicts (fatwas) by Iran's top religious leader, Ayatollah Ali Chamenei, confirming the incompatibility of weapons of mass destruction with Islamic teachings, there was a growing suspicion that the Iranian nuclear-enrichment program was being used not only for peaceful, but also for military purposes. However, throughout the duration of this security crisis, this suspicion was never conclusively proven to be true.

The agreement was negotiated particularly to prevent Iran from enriching its uranium to the level of 90% and acquiring plutonium, as these are the two main components needed to produce nuclear weapons. Prior to the reaching of the agreement, the country enriched its uranium to a maximum level of 20% by using the centrifuge system within the nuclear-fuel complex.

According to the agreement, Iran agreed to reduce the number of installed centrifuges by about two-thirds, and reduce the total stored quantity of low-enriched uranium from 10,000kg to 300kg of uranium enriched to the level of 3.67% for 15 years. All excess centrifuges and enrichment infrastructure will be placed in storage areas monitored by IAEA inspectors. The country will also not build new uranium enrichment facilities for 15 years and will not enrich uranium at Fordo for at least the same period of time. The enrichment facility in Fordo will be converted into a nuclear, physical, technological and research center. The enrichment process will thus only take place in a facility in Natanz for ten years. The condition of avoiding plutonium production is related to Iran's obligation to stop the construction of a separation facility together with the associated construction of a heavy-water nuclear reactor in Arak. If Iran confirms its interest in a military nuclear program, all these and other measures will prolong the time period for getting enough nuclear fuel to produce a single nuclear weapon, the so-called breakout time, from the current 2-3 months to at least 1 year. This should be a sufficient time period for taking appropriate countermeasures. This would be the case if Iran opted for this option, and it would entail the risk of immediately restoring a sanction regime against Iran with a devastating impact on its economy or, in the extreme case, using military methods to resolve the security crisis.

It should be emphasized that the agreement requires Iran to ratify the Additional Protocol to the current General Safeguards Agreement with the IAEA, which will allow inspectors to carry out very thorough checks of its facilities, inter alia, without any prior notification of the place and time of the implementation of the inspection. Thus Iranian nuclear facilities will constantly be subjected to inspections even after the set deadlines and the expiry of the agreement. Similarly, this is also the case for other Member States of the NPT with civilian nuclear facilities and a nuclear/fuel cycle, such as Brazil, Sweden and so on.

UN Security Council Resolution 2231

In accordance with the JCPOA , the UN Security Council adopted Resolution 2231 in July 2015, to which the text of the agreement with five annexes was added. In the resolution, the UN Security Council, among other things, welcomes the agreement, requests that the UN member states and regional and international organizations support its implementation, calls on Iran to fully cooperate with the IAEA and outlines the procedure for the loosening of the UN sanctions. According to the text of the resolution, its provisions should expire 10 years after its adoption on the basis of the confirmation of the fulfillment of the obligations set out in it. Iran's nuclear issue should then be removed from the agenda of the UN Security Council. However, in relation to ballistic missiles, which are not directly related to the Iranian obligations under the JCPOA, the resolution calls on Iran to refrain from activities in the field of these controlled missiles, which can be "used as nuclear weapons´ means of delivery". The current ongoing Iranian missile tests have not shown any violation of the commitment not to carry out tests of nuclear weapons´ means of delivery..

Opponents of the agreement

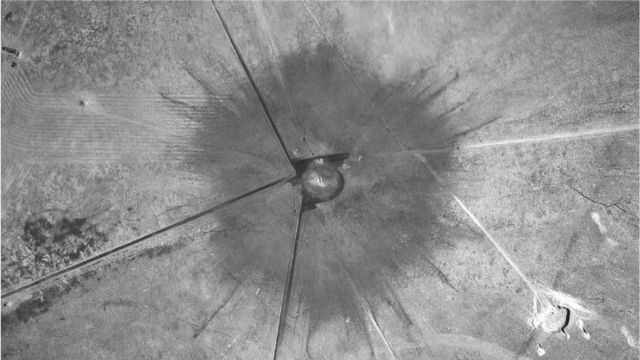

During the negotiation of the agreement and after its approval, the main foreign opponents of the agreement have been Israel and the Sunni Arab countries of the Persian Gulf led by Saudi Arabia. Both of these countries, in the years leading up to the negotiation of the agreement, also urged the Obama administration to carry out US military strikes on Iranian nuclear facilities to resolve the situation. Israel also did not rule out the possibility of it carrying out a possible military action by itself, as it did in the cases of the attack on the Osirak nuclear reactor in Iraq in 1981 and the attack on a reactor that was still under construction in Syria in 2007. On the other hand, those who spoke out against solving the problem by force at the time included especially several former high-ranking American and Israeli military and intelligence officials, who especially warned of the possibility of widening the conflict so that it would cover the whole Middle East region with virtually limitless consequences. The then US President Barack Obama, especially after the disastrous experience of the results of the 2003 invasion of Iraq, quite clearly preferred a diplomatic solution to this problem. In Iran, favorable conditions were created for the negotiation of the agreement, especially after the election of the moderate cleric Ayatollah Hasan Rouhani to the post of president in June 2013.

In the US, the main opponents of the agreement included Republican and some pro-Israeli Democratic congressmen, and the influential pro-Israel lobbying organization AIPAC. In Iran, it was especially representatives of conservative religious groups and some senior officials of the Revolutionary Guard who expressed skeptical views about the deal. The supreme spiritual authority of Iran, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, initially approached the deal with restraint, but eventually came to support the negotiations about it.

The non-certification of the agreement by President Trump on the 13th of October 2017

In the time before President Trump's expected speech regarding the agreement, US Defense Secretary James Mattis and some other members of his administration and advisory board, among others, spoke out in favor of the continuation of the agreement. The representatives of all other countries that were signatories to the agreement, including British Prime Minister Theresa May, German Chancellor Angela Merkel, French President Emmanuel Macron, and the EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy Federica Mogherini, also expressed their support for the agreement. Surprisingly, the agreement was also backed by the former Israeli Prime Minister and Defense Minister Ehud Barak.

However, in accordance with the aforementioned US legal process, which the JCPOA does not mention at all, as the control of its carrying out lies solely with the IAEA, on October 13, 2017, President Trump did not issue a certificate for Iran’s compliance with the agreement. This happened despite repeated IAEA confirmations of Iran's implementation of the agreement.

At the beginning of his speech in connection with this issue, President Trump noted, inter alia, that the agreement is inconsistent with the US security interests. He also pointed out that after the agreed delivery dates would pass, Iran would have an open path to launching a new military nuclear program, and that the agreement does not allow for the entry of IAEA inspectors into military facilities (author’s note: this would actually be contrary to the rules and the role of this organization not permitting inspections of military installations). He further accused Iran of not meeting the spirit of the deal by engaging in various subversive actions in the Middle East region, supporting terrorism and continuing in its rocket tests. However, the president did not mention the significant share of Iran in the fight against the so-called Islamic State in Syria and Iraq.

The US Congress has the next move

In its decision about this matter, Congress will evidently have to respond to the contradictory nature of Trump's decision: although he did not give a certification to Iran’s compliance with the agreement, at the same time he did not appeal to Congress to resume the anti-nuclear sanctions against Iran, which would probably lead to a significant disruption of the implementation of the agreement. Trump, however, did ask Congress to define the conditions under which the sanctions could be imposed if Iran fails to meet its obligations.

Thus, it can be said that President Trump's decision continues to involve the United States in the agreement, but at the same time it poses a serious threat to its continued existence. The purposeful blaming of Iran for its hostile activities not directly related to the provisions of the Iranian nuclear agreement, like that in President Trump's speech, could serve as a guide for the Republican-controlled Congress in setting out the other mentioned conditions.

It is to be expected that for Iran, as well as for the other parties to the agreement, Trump’s decision will be a major obstacle to the further continuation of the agreement, because they unambiguously reject any new negotiations in regard to it. In the opinion of the American lawyer Dan Joyner, Congress could, in an extreme case scenario, formally abolish the US consent to the JCPOA by reapplying the anti-nuclear sanctions and initiating the snapback mechanism under UNSCR 2231 to reintroduce the sanctions of the UN Security Council. Operational articles 11-13 allow any permanent member of the UN Security Council to initiate such a process in the event of a significant Iranian default. Most likely, however, this way of proceeding would not gain the support of the UN Security Council.

It is not yet clear how Congress’s further approach to the agreement could be influenced by the mutual aversion between the President and some influential Republican members of Congress, such as the Chairman of the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations Bob Corker. It is also hard to foresee how far Congress's decision is going to be swayed in the direction of continuing the agreement by an open letter of 25 former foreign ministers and participants of the regular ministerial forum in Aspen to the heads of the US legislative body. The letter was signed by, among others, Madeleine Albright from the USA, Joschka Fischer from Germany, Hubert Védrine from France, Malcolm Rifkind from the United Kingdom and Šlomo Ben-Ami from Israel. More than 90 leading US nuclear experts also sent a similarly worded letter to Congress.

However, if the worst-case scenario occurs by the US taking measures to bring the agreement to a collapse, a deepening of the US's international isolation cannot be ruled out. The reason for this is that both European and non-European members of the United Nations, i.e. France, Great Britain, the PRC, and the Russian Federation, and also Germany and the European Union, continue to support the JCPOA and are also interested in continuing to develop trade and other relations with Iran. Undoubtedly, the US credibility will also be diminished in terms of its meeting its agreed upon commitments. Such developments could, among other things, have a negative effect on efforts to diplomatically settle the controversial issues in the US-North Korean relations. The expected withdrawal of Iran from the agreement and the restoration of its nuclear program could lead to a downturn in the hopeful rise of moderate forces in the country in favor of conservatives. As a result, the crisis in the Middle East region could further sharpen, and the escalation of the assertiveness of the United States and its key allies towards Iran in this area may eventually lead to a possible direct military confrontation.