Analyses - The Shifting World 2024

We are bringing the new Analyses - The Shifting World 2024. This time our researchers have focused on the impact of power competition on world politics. The chapters focus on the role of clash of powers in various world regions.

Obsah / Content

- Mats Braun - The Ukraine EU Membership Bid

- Pelin Ayan Musil - How Türkiye’s Balancing Strategy Between Russia and the West Matters

- Ondřej Ditrych - Setrvačník nebo zemětřesení: geopolitika prezidentských voleb v USA

- Daniel Šitera, Katarzyna Kochlöffel - Triumphalism Eroded: Central Europe After the Poland and Slovakia Elections

- Jan Švec - Česko by mělo vypracovat komplexní plán pro posílení strategické autonomie

- Ondřej Horký-Hlucháň - What Do the Shifts in US and Chinese Engagement in Africa Mean for the EU and Czechia?

- Martin Laryš - Ruská geopolitická expanze v subsaharské Africe po roce 2022

- Matúš Halás - Breaking the Deadlock on the Next NATO Secretary General

- Jan Daniel - The EU in the Middle East Amidst the Great Power Competition and the War in Gaza

Úvod / Introduction

The Movements of Global Politics

The “global order” as a set of norms, rules and patterns of practice undergoes accelerated transition. That very simple fact means that conventional wisdom loses its purchase. We are entering a new era but the break with the past is gradual, and comparisons with past periods risk to mislead. New conceptual categories need to be devised – if not to cast a net to catch the world, then to trace the movements of global politics to meaningfully define and then promote a state’s national interest.

Many such concepts are traded. Too often they betray their authors’ analytical biases, political agendas or just simply following fashionable streams of thought. Take concepts like multipolarity, fragmentation, contestation, or deglobalisation. What does it mean to say that the world is multipolar when in terms of national resources that can be mobilised the U.S., followed by China, are far ahead other powers? Or fragmented and deglobalised when economic and social life is shaped by global flows more than ever? Or contested when indeed, geopolitical revisionism is a fact of global life, but in various intensities and scales, and many seek to operate (and granted, improve their lot) within the existing order rather than imagining radical political alternatives (take the case of China)?

The world is post-unipolar. This means that following a historically short and exceptional moment after the implosion of the USSR in the conditions of a deferred rise of China, the U.S. enjoyed a moment of uncontested primacy in world affairs. That, to remember, never meant a lack of resistance to the hegemonic power projection, but one where this resistance was pushed to global peripheries or practiced in indirect ways. Now, the U.S is not indispensable anymore, and power is more diffused – but clearly not to the point that a number of comparable poles would emerge.

This diffusion translated into a weakening power to bind and to order. The result is more normative pluralism on one hand and a more articulated resistance to liberalism on the other, the latter evident both at the level of revisionist powers and transnational illiberal networks. This dynamic provides more leeway for middle powers and others to shop for patronage and other resources independently or assert their influence as the hegemon’s capacity to restrict their ability to freely manoeuvre fades.

Such structural condition produces ambition, projected in concepts such as multipolarity – and other visions of the global order that give justice to the changing balances of power. The Kremlin skilfully instrumentalises this emancipatory drive as it did in the past, dusting off the Cold War playbook. However, despite its rhetoric promoting a multipolar order and the use of hybrid strategies to maintain global influence, it is far from playing at the high table of global politics. That makes it distinct from China whose global ambitions are backed by the resources of an economic powerhouse, even if it is not unshakeable as demonstrated e.g. by the severe decline in Chinese loans in Africa caused by more austere domestic policy in the face of the current economic challenges.

The condition produces also fear, anxiety, insecurity and defensiveness. They stem from a loss of control, or at least limited ability to shape global processes. It is real, but also inflated through a nostalgic comparison to a fictional past when such control and ability were near to uncontested. It is inflated also by the propensity to deal in (moral and other) absolutes and binaries that obscure the complexity of global politics with its many shades, and understanding of the practice of mundane geopolitical opportunism now practiced by many states’ elites – because they can. The more positioning against Western hegemony and imperialism is palpable. But the “rest” does not revolt against the West – simply because these are not consolidated, defragmented blocs like those that feature in historical dialectical political theories. Instead, there is a multiplicity, one that is not new but one that is just more intense and so visible on the surface.

The BRICS+ is a case in point. It features actors keen on fundamentally revisiting the global order (China), but also those who simply see opportunities in this form of integration to climb the geopolitical ladder, or resist dollar hegemony (and how the U.S. uses it to its geopolitical advantage on their account). Indeed, BRICS+ combined feature impressive economic power. But politically, there is little to unite the members, prone to experience more tensions due to inside attempts to assert predominance by some members that inevitably clash with the bloc’s general emancipation programme. A declared revolt against power – in harmony with reason and justice – easily turns into aspiration for power.

It is both intellectually unsatisfactory and politically misleading to treat global politics with a sense of false nostalgia for the bygone liberal, rules-based order and to seek to impress the (alleged) past simplicity back onto it. Even in its heyday this order featured alliances of liberal and non-liberal forces, was inscribed with the U.S.’ exceptionalism, and was subject to fierce resistance. It is no better to simply state its complexity and resign on resisting the forces of imperialism, technologically enhanced authoritarianism and mass murder conducted in the name of alleged moral purity or social justice. The global order is not at a transit station – a single point of a momentary, dramatic decision that will determine its future. It does depend, however, on the reasons and practices of a multiplicity of actors – including smaller states and their “small labours” – who all co-create it, shaping its continuous becoming in one direction out of many.

To act successfully on the world, in other words, presupposes a good reading of the world. In the nine chapters of this volume, we seek to provide a diverse set of analytical insights into the movements in the contemporary global politics from independent scholarly perspectives that, in the spirit of the mission of the Institute of International Relations Prague and the aims of the TA ČR CURIE project of which the volume is an outcome, broaden the horizons of the public debate and contribute to more competent policy making.

No totalising concepts were imposed on the authors of individual chapters. That said, their explorations all, in one way or another, speak to the issue of great power competition. The great power competition is here not conceived – as it is sometimes the case – as just a new branding for Realpolitik, with a concealed appeal for “geopolitical” foreign policy that brackets ethical considerations for the sake of success in the global battle for influence. Instead, we think of it as a framework to make sense of the various (and nonlinear) effects of the weakening of established ordering mechanisms in global politics, and of the scope and intensity of the resulting competition across its different domains in which relative importance of different resources varies (also over time). The contributions choose and analyse a variety of subjects within this framework: some look at individual actors (Turkey, China, Russia), others at entire regions (i.e., Middle East, Sub-Saharan Africa), yet others on Western responses to current realities in global politics, or on how domestic political variables can shape them over the longer term.

The collection opens with a chapter by Mats Braun in which he argues that there is a momentum for EU enlargement that, however, risks being short-lived. The geopolitically driven enlargement process is likely to gradually become more challenged through arguments referring to costs and the need for EU institutional reforms. The chapter examines the Ukraine membership bid and suggests that if applied correctly, a staged approach to enlargement can speed up the process. Czechia traditionally belongs to the proponents of enlarging the Union and one of the strongest arguments for this at the time of war in Europe refers to the EU’s historic commitment to Europe.

Pelin Ayan Musil discusses in the next chapter Türkiye’s role as a middle power in the global great power competition, particularly in the context of its interactions between Russia and the Western bloc comprising the EU and NATO. The piece highlights a recent shift in Türkiye’s balancing act, with tensions escalating with Russia and improved interactions with the West following President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s consolidation of power in the recent national elections. While the EU strategy aims to enhance relations with Türkiye, potential obstacles include far-right influences, reliance on Russian gas, and Türkiye’s ambition to assert leadership in the Muslim world with an anti-Western rhetoric. Even though Türkiye’s further alignment with the West has positive implications for the Czech Republic, Musil calls for cautious optimism considering the challenges and complexities involved.

In his chapter, Ondrej Ditrych looks at the U.S. presidential election as likely the most significant domestic political event of this year in terms of the impact on global politics and the future faces of great power competition. He sketches two likely scenarios (Biden and Trump victories) and thinks through their international repercussions. In neither case, he concludes, can the revival of U.S. hegemony be expected – and the EU must not fail to prepare for this fact and overcome addiction on the U.S. as a security provider as well as resist own sliding toward national sovereigntist solutions.

In their chapter, Daniel Šitera and Katarzyna Kochlöffel use the 2023 elections in Poland and Slovakia to stress the complexity of Central European politics. The authors argue that the debate about how the centre of gravity in European decision-making is moving to the centre/East of the continent has been misleading. The divergent outcomes of the elections show the need to take domestic politics seriously to understand the foreign policy of the region. Even if the support for Ukraine is strong, it is at the same time challenged. Fico’s election in Slovakia as well as the Polish farmers’ protests on the border to Ukraine points to a reluctance to bear the costs of Russia’s war in Ukraine in a part of the society. Moreover, the authors stress that expectations of pro-EU Polish foreign policy should be realistic.

In his chapter, Jan Švec sheds light on the EU’s dependence on China in its transition towards climate neutrality. He emphasizes China’s dominance in key areas such as the extraction and processing of essential raw materials, manufacturing of electric cars and production of solar panels. Švec emphasizes the increasing vulnerability of the Czech Republic in this context, given its economic dependence on the automotive sector, making it susceptible to global supply chain fluctuations. He calls for the formulation of a comprehensive plan to promote technological innovation and encourages international collaboration to safeguard the Czech Republic’s strategic autonomy, in harmony with the EU principles on climate neutrality.

Ondřej Horký-Hlucháň’s analysis delves into the shifting dynamics of the U.S. and Chinese engagement in Africa and their implications for the EU and the Czech Republic. Since China decreased its bilateral lending to Africa, the U.S., under Biden’s administration, has shown renewed interest in the continent, although without dedicating much additional resources. The EU, despite being a major actor in Africa, faces challenges in its approach, ranging from bureaucratic rigidity to lack of coherence as exemplified by the Global Gateway initiative. The author emphasises the need for the EU to achieve coherence across its policies, highlighting the parallel challenges faced by the Czech Republic and the U.S. in resource allocation in the region. The analysis calls for enhanced EU-U.S. coordination to address shared concerns and support African development, and urges the Czech Republic and other member states to contribute to policy coherence and allocate resources effectively.

The following chapter by Martin Laryš explores Russia’s efforts to geopolitically expand in the sub-Saharan Africa through the use of diplomatic, military-security and symbolic tactics. Russia attempts to present itself as an ideological counterweight to Western values, and despite being a minor economic player, it gains influence through offering inexpensive military-security services. Laryš suggests that Russia’s resources may limit its ability to sustain expansive influence in the future, possibly leading to a focus primarily on the Sahel region in the short term. In terms of the implications for the Czech Republic, he highlights the potential of efforts to counter pro-Russian narratives in sub-Saharan Africa, in collaboration with the EU member states in Central and Eastern Europe such as Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia and Romania. Such collaboration, he concludes, emphasising shared historical experiences and opposition to expansionist policies, has the potential to strengthen the EU’s links with societal actors in the region.

Matúš Halás then turns the attention to closer home. In his chapter, he looks into how the deadlock over the choice of NATO’s next Secretary-General could be broken, and where do Czech interests lie in this endeavour. Jens Stoltenberg will leave a major footprint on the Alliance history, but this is not to say that his successor’s tasks including strengthening the Eastern Flank and securing longterm support to Ukraine will be insignificant. Having reviewed the selection criteria and candidates’ landscape, Halás concludes by weighing relative merits of three female candidates from the Central and Eastern Europe: Zuzana Čaputová, Kaja Kallas and Luminita Odobescu.

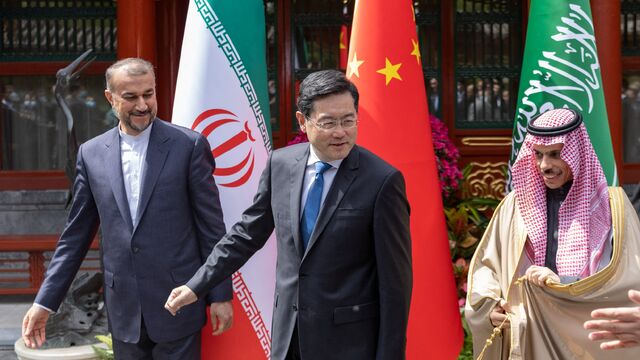

The collection closes with Jan Daniel’s chapter looking into the EU’s position in the Middle East now undergoing a major turbulence as a result of the Hamas attacks and Israel’s military operation in Gaza in the conditions of rising regional multipolarity and increasing engagement of third powers (Russia, China) as the U.S. footprint has been downgraded over time until recently. Daniel reviews critically the EU’s response to the war and concludes that pragmatic engagement by regional actors with outside powers will likely continue but the EU’s position has been further eroded as a result of its inability to arrive at a unified and constructive response.

(Tato analýza je výstupem projektu TL05000626 „Odborná komunikace jako nástroj posilování společenské odolnosti v postfaktické době“, podpořeného technologickou agenturou čr. nositelem projektu je Ústav mezinárodních vztahů, v. v. i..)