A Manifesto For The Czech Membership In Nato’s Nuclear Sharing Club - Analyses IIR

In his contribution to Analyses IIR, Matúš Halás focused on the prospects of Czechia's security policy, which should adapt to a new environment shaped by the Russian aggression in Ukraine.

Czechia should join the NATO nuclear sharing programme within the next ten years in order to accomplish a full adaptation of its security and defence policy to a new environment shaped by the ongoing war in Ukraine. This process of a gradual adaptation started already before the Russian invasion of February 2022 and it transcends the domestic political divisions between virtually all the major political parties. Yet the war exacerbates previous trends. The relations between Prague and Moscow are now at their all-time low, the Western countries all support Ukraine, although to various degrees, and any possible future NATO-Russia cooperation will have to be established de novo. The practice of a large-scale conventional war returned to Europe, and mixed signals are pouring in from Russia, even with respect to the use of tactical nuclear weapons.

The Czech policy has to adapt to that. Considering all the relevant contextual factors of Czechia that are listed below, it is time to define the Czech security and defence role vis-à-vis its partners as that of a net contributor. Since NATO is the most important institutional setting for Czechia as regards its external security, such an ambition would imply an appropriate contribution to NATO’s deterrence and defence posture across the board at all capability levels. Prague is already an important contributor to credible security guarantees of the Alliance at the conventional level, especially with respect to the Eastern Flank. It would be timely to enhance this contribution so that it would include also the nuclear level. Joining NATO’s nuclear sharing club is thus a natural choice for Czechia.

AUTOCRATS ARE NOT OUR PARTNERS

The foreign, security, and defence policy of Czechia turned more assertive and principled in recent years. In the past, it was characterised by an effort to hold the line with the West as to respect for human rights and democratic freedoms while simultaneously trying to develop pragmatic relations with non-democratic countries like Russia and China based on a mutually beneficial cooperation. This position, fuelled by various economic dependencies and a prospect of trade opportunities, has been common in many European countries. In the Czech context, it frequently transpired into a division between a more principled position of the Government and a more pragmatic stance of the President, as illustrated by the meetings between Miloš Zeman and Xi Jinping or the President’s position with respect to Crimea and the sanctions against Russia. This era seems to be nearing its end, however.

The Western approach toward non-democratic regimes like Russia and China is undergoing a transformation and Czechia takes part in it. At the global level, the administration of Donald Trump accelerated the shift to a more assertive policy vis-à-vis Beijing, and the unprecedented visit of the Czech senate president Miloš Vystrčil to Taiwan in August 2020 has been a watershed event in the Czech context. This would not have meant a lot under normal circumstances since Vystrčil then belonged to an opposition party (ODS). Yet, a few months later, in April 2021, the government of Andrej Babiš (ANO) announced that Russian foreign military intelligence has been responsible for the 2014 explosions of ammunition depots in Vrbětice. The mutual relations then swiftly deteriorated. Prague expelled 18 employees of the Russian Embassy and Moscow established a list of unfriendly nations with Czechia included in it. Czechia’s hardening stance toward non-democratic regimes is also illustrated by a shift away from the previous policy of not naming and shaming specific countries in the Czech national security strategy. The new government of Petr Fiala (ODS) then had

to deal with the Russian invasion of Ukraine during its first 100 days in office.

The war prompted an adaptation of security and defence policies across Europe. Sweden and Finland quickly asked for NATO membership while the entire Eastern Flank of NATO has been reinforced with additional capabilities. The commitments of the Alliance stemming from the NATO-Russia Founding Act of 1997 appear particularly counterproductive in this context. It is not only that Russia violated its obligation to respect the “sovereignty, independence and territorial integrity of all states,” but NATO’s own declaration that it has “no intention, no plan, and no reason” to change its nuclear posture as well as its commitment not to permanently station “substantial combat forces” in the new member states now directly contradicts its own security interests. Czechia has to adapt to that.

TRANSFORMING THE CZECH MILITARY

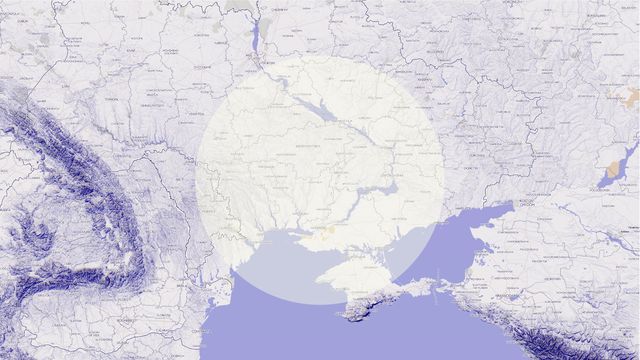

The immediate result of the increasingly assertive Czech policy toward non-democratic regimes and the changes to Czechia’s security environment, has been a remarkable willingness to invest in its own defence capabilities and help Ukraine and other partners militarily. Since February 2022, Prague either declared its intention to buy, was promised to receive, or already decided to purchase two dozen F-35A fifth generation multirole fighter jets, hundreds of CV90 tracked infantry fighting vehicles, Leopard 2A7+ main battle tanks, some additional UH-1Y utility and AH-1Z attack helicopters, and hundreds of Tatra heavy trucks. Besides that, the Czech Air Force took part in the Baltic Air Policing from April to September 2022 and since then it jointly patrols with Poland the sky over Slovakia. Two hundred Czech soldiers contribute to the NATO enhanced Forward Presence in Lithuania and Latvia, and since April 2022, Czechia is also the framework nation of the multinational battlegroup in Slovakia established after the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

A very similar picture is offered by an analysis of the Czech military help to Ukraine. Prague provides Kyiv with a continuous supply of weapons and ammunition. Ukraine is about to receive or is already using more than one hundred Czech T-72 tanks in various configurations, dozens of BMP-1 infantry fighting vehicles, several Mi-24 attack helicopters, dozens of self-propelled tracked (Gvozdika) and wheeled (Dana) howitzers,

multiple RM-70 rocket launchers as well as various small arms and other military hardware from Czechia. Not to mention the fact that up to 4,000 Ukrainian soldiers underwent or will undergo military training in Czechia in 2022 and 2023 as part of the corresponding EU-led initiative. Yet the contextual understanding of this military help is maybe even more important. Only the United States, the United Kingdom, Poland, Germany, and Canada offered Ukraine substantially more military help in absolute terms. In relative terms, if the military help is expressed as a share of bilateral aid in the given country’s GDP, the Czech Republic tops the list in this respect together with the Baltic States, Poland, Slovakia, Norway, the USA and the UK. Czechia thus stands out as the greatest donor that is simultaneously not an Eastern Flank frontline nation out of all the Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries of NATO.

BECOMING A NET SECURITY CONTRIBUTOR

All these trends at the domestic as well as international level reinforce each other and set Czechia apart from its neighbours. Unlike many Western European countries, Prague has been increasingly assertive towards non-democratic regimes, even before February 2022, and this was the case across the entire party system. It is willing to help Ukraine at a scale comparable only with those of Poland and the Baltic states, yet unlike them, it is not a frontline nation. Its economic performance and democratic track record are exceptional, and again this sets Czechia apart from other CEE countries that joined NATO and the EU around the same time. Given the fact that NATO is probably going to significantly revise its deterrence and defence posture in the coming years as a response to the war in Ukraine, Czechia is therefore uniquely positioned to accomplish a full adaptation of its security and defence policies to this by finding a new, appropriate

role within the Alliance.

The most suitable role for Czechia vis-à-vis its partners and allies on the Eastern Flank in particular would be the one of a net security contributor. But to contribute more to credible security guarantees than what it would receive in return would require taking on more responsibilities across different domains. And since Prague already helps significantly on the Eastern Flank at the conventional level, it would be only natural for it to go beyond that and start contributing also at the nuclear level by joining the NATO nuclear sharing programme. This would not only reinforce the Eastern Flank, but also help overcome the artificial division between old and new member states as defined in the now defunct NATO-Russia Founding Act. An eventual procurement of 24 F-35As certified for the B61-12 nuclear gravity bomb would then make even better sense.

JOINING A NUCLEAR SHARING CLUB

The transformation of the European security environment caused by the war in Ukraine, together with a gradual shift toward a more principled and assertive Czech foreign policy, will enable Prague to adopt a new, more ambitious role in security and defence. Joining the NATO nuclear sharing club would be a natural choice for Czechia in this context. It will require increased investments in military infrastructure, overcoming possible resistance at the international level, and an ability to cope with protests against hosting foreign troops on the country’s territory. However, a domestic political consensus and the country’s tradition of meeting high standards of democracy and human rights might help overcome these obstacles over time. The similar ambition of Poland and the expected support from other CEE countries could make things easier for Prague too.

→ The developing security environment in Europe asks for a comprehensive adaptation of the Czech security and defence policy.

→ Czechia’s new role as a net security contributor vis-a-vis its allies shall form the core of this Czech adaptation across the board.

→ The Czech Republic should join the NATO nuclear sharing club within the next 10 years to accomplish this adaptation.

The chapter was published in this year's annual publication "Svět v proměnách 2023: Analýzy ÚMV".