The 2020 US Presidential Elections and the Geopolitical Implications for Central and Eastern Europe

The overwhelming domestic developments in the United States have sidelined questions related to foreign affairs within the current presidential campaign. Though foreign policy is a marginal issue on the voters’ minds and given that the election results might be extremely close and perhaps decided by only tens of thousands of voters in key battleground states, it must nonetheless be noted that the 2020 elections may reaffirm an irreversible course for US foreign policy that will fundamentally alter the current state of multilateral and geopolitical global ordering.

The first term of Donald Trump’s presidency was characterized in the foreign policy realm by personal and institutional resistance. From “restoring the role of the nation state” in global affairs at the expense of multilateral governance to concluding deals with adversaries and partners alike that would ensure the US is no longer being “cheated” and “ripped off”, Trump struggled with a line of National Security Advisors, and Secretaries of State and Defense, who were reluctant to carry out disruptive initiatives he sought to implement. A second Trump term would see more consolidation of personnel and conformity leading to groupthink and thus more willingness to implement the president’s intentions.

The conception of US “leadership” in global affairs would further disintegrate, leaving room for possible revisionism of global norms. Withdrawal from multilateral engagements involving a decoupling with the European Union would continue at a faster pace. The Trump administration does not subscribe to the postwar liberal internationalist paradigm, which holds the view that open and interdependent economies and democratic political systems make for stable and peaceful relations. In fact, the administration sees liberal internationalism as a threat to US sovereignty, self-government and even the economy. So, while US support for a politically and economically integrated Europe fits perfectly into the liberal internationalist perspective, beyond the bounds of this worldview the EU suddenly becomes a geopolitical and economic competitor for the US.

Still, Donald Trump does not intend to preside over a period when US hard power and global influence diminishes, which is difficult to reconcile with the transactional and unilateral diplomatic approach he has chosen. Nonetheless, the implicit fear of the loss of US status and prestige among the international community leads the Trump administration to hedge and protect its turf against the geopolitical encroachments of competitors and rivals. This attracts the administration’s focus toward Central and Eastern European states (CEEs), which are viewed once again as “contested” territory.

A former US Assistant Secretary of the Bureau of European and Eurasian Affairs, A. Wess Mitchell, expressed the American pivot to Eastern Europe in the following manner: “Our Europe strategy begins by acknowledging that Europe is once again a theater of serious strategic competition and needs to be treated as such […] One place where strategic competition is intensifying dramatically is on Europe’s Eastern frontier”. Also, during one of his visits to the Visegrad Group states, US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo indicated that US “absence” in the region in the recent past drove the countries to “fill a vacuum with folks who didn’t share our values” and as a consequence the “Russians and the Chinese ended up getting more influence”.

Not only do Central and Eastern European leaders manifest a level of ideological proximity to the administration’s worldview and political tactics in general, they are also more prone than their Western EU counterparts to depersonalize US policies from Donald Trump’s persona. Consequently, the CEEs demonstrate readiness to assist the US in countering geopolitical challenges.

For instance, in regard to technological competition with China, Washington has readily accepted Prague as one of its lead partners in establishing ground rules for operationalizing 5G infrastructures. Recently, the US Congress embraced the “Prague Proposals”, which compose a set of recommendations for states to consider as they design, construct and administer their 5G networks. Amidst growing German reluctance to host US troops on its soil and as a deterrence measure against Russia, Warsaw has offered to construct “Fort Trump” and welcome a large presence of US military personnel. Moreover, as a counterweight to the Chinese offers of infrastructure funding and development under the “One Belt, One Road” initiative and its 17+1 scheme that aims to induce Eastern European states into cultural and economic cooperation with China, Washington has begun to be a fond supporter of the Three Seas Initiative. Originally a Polish concept for order and cooperation in Central and Eastern Europe (Międzymorze), the Three Seas Initiative associates twelve states in Central and Eastern Europe with the aim of supporting projects in the energy, transport, digital communication and economic sectors. Visiting the Czech Republic in the summer of 2020, Pompeo reaffirmed that the US would commit 1 billion USD to the Three Seas Fund to support infrastructure projects. Additionally, the administration has allegedly nudged the European 17+1 member states to quit the Chinese-led initiative. These examples point to the conclusion that geopolitics, again and unsurprisingly, appears as the most workable rationale for fostering transatlantic ties in the 21st century.

A second Trump term would consequently drive a geopolitical wedge between CEE and Western EU member states. While France and Germany would – at least rhetorically – even more vehemently seek strategic autonomy, the CEEs would be reluctant to further decouple from US security guarantees, especially since the notion of European strategic autonomy is meaningless unless Germany decides to rearm.

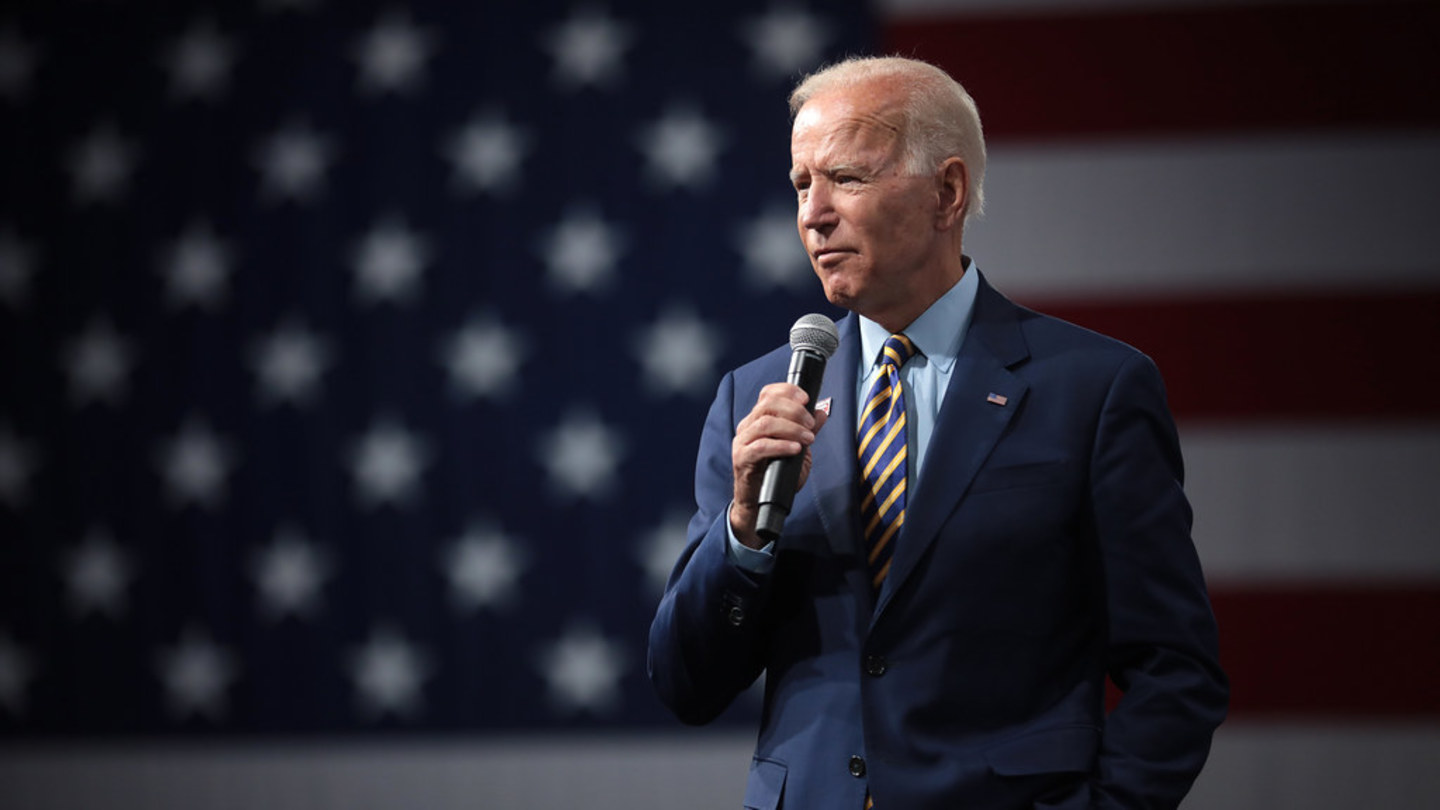

Of course, the question remains of how a possible Joe Biden victory would change the dynamics of current CEE-US relations. Biden himself and the team of advisors that would likely surround him are considered to be “traditionalists”. They generally believe in the liberal internationalist paradigms and in the organization of the postwar order. The perpetuation and restoration of “US leadership” in the world would be the narrative framework within which the Biden administration would conceive of its foreign policy. Yet a domestic debate would have to occur in order to confront the strong protectionist, sovereigntist and nationalist voices empowered by the Trump presidency; thus the restoration of US leadership would mostly begin at home. In this sense, a Biden presidency would find more common ground with Western EU member states and thereby reorient the United States’ Europe policy from the CEEs toward Brussels. Though a Biden presidency would commit more strongly to a united Europe and to maintaining the transatlantic partnership, the CEE states would lose a portion of their newly acquired strategic relevance for the US.

American voters will thus impose one of two scenarios upon the Central and Eastern European states, each with its own caveats. During a second Trump administration, the CEEs could face unprecedented interest from Washington, which would be accompanied by the diplomatic, economic and security benefits traditionally associated with US engagement. However, the trade-off would be a continuation of the incremental deconstruction and delegitimization of contemporary multilateral rules and norms. A Biden presidency would aim for a return to global “normalcy” (meaning the restoration of US leadership and liberal internationalist outlooks), which the CEEs would on the one hand welcome as order based on multilateralism is generally beneficial to smaller states, but on the other hand they would see their position shifting back to a rather peripheral status within the US Grand Strategy. Neither of the two scenarios, however, presents an optimal development of international security and order for the Central and Eastern European states.

Mezinárodní Politika has established cooperation with the Peace Research Center Prague, a newly established interdisciplinary center of excellence at the Charles University, with focus on prevention, management, and transformation of conflicts in world politics. This article is part of the policy brief series published by the PRCP and Mezinárodní Politika. For more information, visit http://prcprague.cz.