How Should Europe Address Iran’s Missile Proliferation Activities?

paper

One of the criticisms that has been leveled at the Iran nuclear agreement officially known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) reached with the world powers in 2015 is that it failed to address Iran’s ballistic missiles. The ballistic missile programme provides the means for nuclear delivery should Iran decide to acquire nuclear weapons. Iran’s missile proliferation is particularly destabilizing for the region with detrimental knock-on consequences for Europe.

SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Europe should maintain its pressure on Iran to stop testing missiles that exceed the limits of the Missile Technology Control Regime (MTCR) and transferring missiles to regional proxies. Where Iran continues with its provocations, the EU should impose sanctions on Iranian and third-party organizations involved in the missile programme, reflecting actions it has taken to counter Iran’s human rights abuses. The E3 countries (Britain, France and Germany) should exert their influence to reinforce the EU’s efforts to strengthen coordination with the United States in using diplomatic channels with countries supporting Iran, such as Russia and China, to foster a more robust international response to the missile threat.

The EU should also play a leading role in formalizing constraints on the range of Iran’s missiles. In the short-term, such an agreement would seek to prevent Iran from developing missiles that could strike Europe, with the ultimate objective of broadening restrictions on Iran’s missiles as part of a wider regional arrangement.

INTRODUCTION

Iran has the largest and most sophisticated missile arsenal in the region. Its ballistic missile programme poses a threat to key European partners in the Middle East and by extension to Europe as well. Some European countries are also within range of Iranian missiles. It therefore has a vested interest in addressing this threat.

Iran is believed to be working on three potential options that would enable it to acquire intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs). An ICBM is traditionally defined as possessing a range of 5,500 km or more and could serve as a delivery vehicle for a nuclear warhead posing a direct threat to the United States and Europe. Moreover, Iran’s missile programme, its proliferation activity and the role it has played in supporting its regional proxies are particularly destabilizing for the region because Tehran has shown a willingness to share its capabilities with unaccountable non-state actors that have activated these missile systems.

Ahead of the signing of the nuclear deal, Iran had insisted that it would not discuss its missile programme in negotiations with the world powers. Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei had asserted that it was “stupid and idiotic” to expect Iran to curb its ballistic missile programme. Iran’s president-elect Ebrahim Raisi has asserted that Iran’s ballistic missile programme is “not negotiable”. While it is highly unlikely that Iran would agree to far-reaching constraints on its missile programme, this paper will outline the steps that European countries can take to mitigate the threat it poses.

THE IRAN MISSILE THREAT

Iran has spent many years developing nuclear-capable missiles. The US Director of National Intelligence, James Clapper, asserted in his annual Worldwide Threat Assessments statement in February 2016, that Iran ‘would choose ballistic missiles as its preferred method of delivering nuclear weapons, if it builds them. Iran’s ballistic missiles are inherently capable of delivering WMD’.

Iran is working to enhance the accuracy of its medium-range and longer-range missiles and has also developed cruise missiles designed for attacking land targets. Iran has also strengthened the accuracy of its shorter-range missiles, exemplified by the January 2020 attack on the Ayn Al Asad air base hosting US forces in Iraq. Iran’s ambitious space programme has also received significant international attention because of the technical convergence between ICBMs and space launch vehicles.

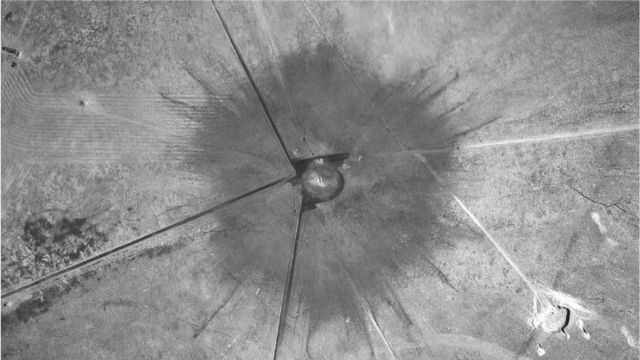

A separate concern is that Iran has exported its missile capabilities to its proxies. These missiles also provide room for independent attacks by nonstate actors in support of their own regional goals, or strikes advancing Iranian interests that are deniable by Tehran. A prime example of this is the combined cruise-missile and drone attack carried out on a Saudi oil facility in September 2019. The Houthis claimed responsibility for the attack but Western intelligence sources claimed that there was no evidence that the attack was carried out from Yemen but rather from Iraq or Iran. Iran has also armed Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad and in recent years has shared its expertise with these organizations. This could be seen clearly during the recent military escalation with Israel in May 2021. As well as providing smuggled parts and weapons, Iran has supplied training to help Hamas improve the accuracy of their rockets and extend their range . Lebanon’s Hezbollah has more than 150,000 artillery rockets and ballistic missiles. Its missile arsenal was used in 2006 during a 33-day war with Israel. In 2020, Hezbollah Secretary-General Hassan Nasrallah claimed that his group was capable of striking the entire country with precision.

European security is affected by the relatively close proximity of Iran to Europe.

Thus, back in 2018 before the US withdrew from the nuclear deal with Iran, Luxembourg Foreign Minister Jean Asselborn stated: ‘Mr. Trump should not destroy the nuclear deal. After all, it is Europe that is within range of Iranian missiles’.

Iran already has missiles that can reach targets in the Middle East, Turkey (a NATO member), and southeast Europe. On 1 December 2018, Iran reportedly tested a medium-range ballistic missile, thought to be the Khorramshahr, which could potentially hit much of southern and eastern Europe and perhaps even France. The Khorramshahr has a range of 2,000 km when carrying a 1,000 kg payload and may be capable of achieving a range of at least 3,000 km if carrying a lighter payload. The Khorramshahr missile has likely been designed to deliver nuclear weapons, as it appears to be derived from North Korea’s Musudan missile which was also developed to carry a nuclear weapon. The threat posed by missiles originating from the Middle East has been a key driver of US efforts to deploy missile defences in Europe. NATO has long maintained that the missile defence system under development in Europe has been established in the light of threats from ‘outside the Euro Atlantic area’.

WHY IRAN HAS RESISTED EFFORTS TO CONSTRAIN ITS MISSILE PROGRAMME

The missile programme advances key Iranian objectives: deterring attacks against Iran, supporting military capabilities of regional proxies such as Hezbollah and the Houthis, strengthening national pride and regional influence, and providing the means for nuclear delivery should Iran decide to acquire nuclear weapons. Iran seeks to ward off adversaries such as Saudi Arabia, Israel and the United States by adopting a ‘deterrence by punishment’ approach. The Western sanctions imposed on Iran since 1979 have hampered Iran’s ability to maintain and upgrade its air force, thereby increasing its reliance on missiles for deterrence and defence. Iran’s experience during the Iran-Iraq war was that ballistic missiles could enable it to offset the military superiority of its adversary. Missiles have become a powerful political symbol for the Iranian regime, as well as a source of legitimacy and prestige, enabling it to assert greater regional influence.

Iran maintains that is unwilling to accept attempts to include its missiles in the nuclear negotiations on the grounds that its ballistic missile programme is “non-nuclear” – it was developed for conventional and defensive purposes, a legacy of the traumatic experience of the war with Iraq in the 1980s. Moreover, some experts argue that the inclusion of Iran’s ballistic missile programme in the negotiations could present new difficulties. Thus, Iran could insist, for example, that Saudi Arabian missile programmes also be addressed.

EUROPE’S RESPONSE TO THE MISSILE THREAT

European countries have opposed Iran’s missile-related support to its regional proxies, and encouraged negotiations aimed at placing restraints on Iran’s missile capabilities and exports. A number of European countries, including Britain, France, Germany and the Czech Republic have shown a growing understanding for the need to impose restrictions on Iran’s missile programme, out of an awareness that it poses risks for a number of Middle East allies and by extension to Europe as well.

The Czech Republic has been particularly vocal in its condemnation of Iran’s missile testing activities. The Czech Republic is one of Israel’s strongest allies within the EU and its support for Israel has been a consistent element in its foreign policy over recent years, reflected most recently in the visit of Foreign Minister Jakub Kulhánek to Israel as a gesture of solidarity during the armed conflict with Hamas. On 10 May 2018, the then Czech Foreign Minister, Martin Stropnicky, stated that the Czech Republic shared the concerns of Israel and the United States regarding the Iranian missile programme. Following the statement of the EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs, Federica Mogherini, regarding the decision of the Trump administration to withdraw from the JCPOA in May 2018, Stropnicky remarked: ‘What I find completely lacking in Ms. Mogherini’s statement is any mention of Iran’s ballistic missile program, missiles which, as you know, can reach targets 500 to 12,000 kilometres away’.

France has been one of the most vocal European countries on the issue of Iran’s missiles. In November 2017, a French Foreign Ministry statement expressed concern ‘about the continued pace of the Iranian missile program, which does not conform with Security Council Resolution 2231 and which is a source of destabilization and insecurity for the region’. The French President Emmanuel Macron has strongly supported negotiations with Iran on the missile issue and expressed his interest in February 2018 for talks to begin with the permanent members of the UN Security Council with the inclusion of regional parties so that the insecurity resulting from Iran’s ballistic missiles could be ‘reduced and eradicated.’ Macron has also called for the imposition of sanctions and controls to address the problem. In 2021, he reiterated his call for negotiations with Iran that would place limits on its missile programme. While there have been few specifics from France in regard to what they would aim to achieve in the talks, the French president has called for a way to be found to include Israel and Saudi Arabia in the nuclear discussions with Iran.

The positions of Russia and China on the issue of Iran’s missile threat pose a challenge for Europe. Russia has vetoed UN Security Council resolutions condemning Iran for transferring missiles to its regional proxies. Over the past thirty years, Iran has obtained components for its missile programme from entities in Russia, China and North Korea. In December 2019, Russia, China, and Iran held their first trilateral naval exercise, Marine Security Belt, in the Indian Ocean and the Gulf of Oman. In March 2021, China and Iran signed a 25-year strategic agreement. Russia is reportedly planning to supply Iran with an advanced satellite system that will enable it to track potential military targets in the Middle East and beyond. Iran could share such satellite imagery with its regional proxies. Furthermore, by gaining access to advanced satellite imagery, Iran would have the means to strike distant targets with greater accuracy.

There is also a separate difficulty in regard to the deadlock between the United States and its European allies on one side and Russia and China, on the other, over perceptions of the threat posed by Iran’s missile programme. This disagreement raises questions over whether the international community can provide a meaningful response to the issue of Iran’s ballistic missile programme. Following the signing of the Iran nuclear deal, UN Security Council Resolution

2231 was approved which watered down the language of previous UN Security Council Resolution 1929 adopted in 2010 to address Iran’s missile programme. Under the previous language, the US and its allies could argue that the UN had formed its assessment of Iran’s compliance in accordance with the spirit of the Missile Technology Control Regime (MTCR) – that any missile with a range of 300 km or more and a payload capacity of 500 kilograms could be deemed WMD-capable. The MTCR was originally created in 1987 in order to curb the proliferation of WMD-capable missiles and to counter the risks of nuclear proliferation by controlling the exports of the major missile manufacturers. Thus, the aforementioned missile tests that Iran has conducted are deemed to have exceeded the limits of the MTCR, although Iran and some other countries question the international applicability of the regime. The United States, France and the United Kingdom maintain that if a ballistic missile is ‘designed’ to be capable of delivering a payload of at least 500 kg to a range of at least 300 km, then it is ‘designed to be capable of delivering nuclear weapons.’ In contrast, China, Iran and Russia maintain that a ballistic missile must be designed precisely for the purpose of carrying nuclear weapons, irrespective of range and payload capability.

HOW EUROPE CAN EXERT INFLUENCE

Restrictions on Iranian missiles imposed under Resolution 2231 will remain in place until October 2023. Previous EU-wide sanctions against Iran helped to restrict its access to the foreign parts and components required for its nuclear and missile programmes. Europe should continue to pressure Iran to stop launching missiles and transferring missiles to regional proxies by imposing sanctions on Iranian and third-party entities involved in Tehran’s missile programme. Earlier in 2021, the EU countries agreed to impose sanctions on Iranian individuals in the wake of human rights abuses. The same approach should animate the EU’s approach towards Iran’s missile provocations. Nevertheless, it is important to be realistic in terms of what can actually be achieved with sanctions. On the one hand, sanctions have been perceived by European policymakers as an effective tool to bring Iran to the negotiating table. Yet Iran has continued to make consistent progress with its missile development activities in spite of the many restrictions it has faced and this isn’t expected to change in the immediate future.

Diplomacy to constrain Iran’s missile proliferation is likely to meet with more success if Russia and China are part of this effort, as they enjoy influence in Tehran. Nevertheless, Russia’s military support for Iran, including the possible transfer of advanced satellite systems, carries the risks of emboldening Tehran in its provocative actions and destabilizing the Middle East. It is therefore in Europe’s interest to strengthen coordination with the United States on policy towards Russia. Europe should work closely with the United States in using diplomatic channels with Russia and China to highlight the regional and global dangers emanating from Iran’s advancing missile programme and persuade these countries to take action to constrain its missile proliferation activities. The influence of the United Kingdom, France and Germany (the E3) could be particularly important here in reinforcing the diplomacy of the EU, laying foundations for European diplomacy in a number of strategic areas. It was the E3 that launched negotiations with Iran over its nuclear programme between 2003 and 2005, reinforcing the EU diplomatic coordination with the United States that eventually resulted in the JCPOA of 2015.

Russia has on occasion shown its sensitivity to international pressures over military support for Iran, exemplified by its decision in 2010 to temporarily suspend the delivery of the S-300 anti-missile system following Western pushback. Multinational forums should be utilized to engage with Russia and to relay concerns over the grave implications of Iran’s missile proliferation. Moscow and Beijing should also be warned that any advances in Iran’s missile capabilities may also accelerate the deployment of missile defences which they strongly oppose.

In recent years, amid the standoff over Iran’s missile programme, there has been a growing call for negotiations to place contraints on long-range Iranian nuclear-capable missiles that could threaten Europe and the United States. According to this view, given the central role that missiles play in Iran’s deterrence, abandonment of the missile programme in its entirety is unrealistic. Instead, Iran should be prevented from developing an ICBM by adhering to the 2,000 km range limit that Iran has already said is its maximum requirement. Thus, the EU should focus on preventing Iran from extending its missile range so that the threat to the continent is minimized.

In response to international pressures, Iran’s Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, has spoken in the past of limiting the range of Iranian ballistic missiles to 2,000 km which would signify that they could only reach targets in the Middle East. This limit is in line with a missile doctrine which over the past decade has changed from relying on punishing potental adversaries by striking cities and other high-value targets, to prioritising improved accuracy in order to deny enemies their military goal.

However, this approach has its drawbacks. By creating distinctions between missiles that threaten Europe and the United States and those capable of striking their allies in the Middle East, Iran may calculate that it need not pay a price for continuing the development of short- and medium range missiles that can be used to attack countries such as Saudi Arabia and Israel. This would send a problematic message in terms of a reduced European commitment to its regional partners, unless it is made clear that a ban on Iranian long-range missiles is just the starting point of international efforts to counter Iran’s missile threat. In the longer-term, an effort to extend restrictions on Iran’s missiles is more likely to work, however, if it is part of a broader regional arrangement.

CONCLUSIONS

Iran’s missile programme, its proliferation activity and the transfer of missiles to regional proxies are particularly destabilizing for the region with harmful consequences for Europe. In view of Europe’s determiniation to counter nuclear and missile proliferation and the concerns, it has over instability in the Middle East, this paper proposes that the EU should take action in coordination with the United States and other like-minded partners to address the threat posed by Iran’s ballistic missile programme.

- European countries will be aware that Iran has continued to make consistent progress with its missile development activities in spite of the many restrictions it has faced. Nevertheless, the EU should continue to exert pressure on Iran to stop testing missiles and transferring missiles to regional proxies that violate the MTCR. Iran should be made aware that there is a price to be paid for the pursuit of provocative and destabilizing missile proliferation policies.

The EU should be ready to impose sanctions on Iranian and third-party organizations involved in the ballistic missile programme, reflecting actions it has taken elsewhere, such as in the case of Iran’s human rights abuses. Such actions will reinforce European credibility by demonstrating a capacity to back up words with action. - The EU can also make a difference by engaging in negotiations with Iran that will culiminate in the formalization of restraints on the range of its missiles. In the short-term, such an agreement would prevent Iran from developing missiles that could strike Europe. Nevertheless, a ban on Iranian long-range missiles should be seen as only the starting point of international efforts to counter Iran’s missile threat.

- Iran is arguably emboldened in its missile proliferation because China and Russia’s support encourage it to believe that it need not pay a price for its actions. It is therefore in the EU’s interest to work in closer coordination with the United States in using diplomatic pressure with Russia and China to highlight the regional and global dangers emanating from Iran’s advancing missile programme. The role of the E3 countries could be valuable in reinforcing the diplomacy of the EU and to persuade Russia and China to act to constrain Iran’s missile proliferation activities