We Need to Talk About China: Uighur Detention Camps and Fragmented Responses from the International Community

The Chinese government has notoriously been running internment camps in the Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region since 2014. Claiming to be “re-education facilities to fight extremism” for the region’s predominantly Muslim population, the release of new information in the wake of a leak made to the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) provides the international community with inside evidence of the cultural genocide being perpetrated by the Chinese Communist Party.

As they are detained without trial and subjected to brainwashing and humiliation, Uighurs and other ethnic minorities are suffering vast human rights abuses. The reaction of the international community has been divided – a number of states have condemned China’s actions, but an equal amount have sided with the PRC and chosen to accept their given narrative. This polarised reaction has resulted in minimal progress being made to hold China accountable for their actions. In order to stop the ethnic cleasning, the international community must use the multilateral procedures that are in place within international law to hold China accountable.

China’s policy towards the Uighur minority

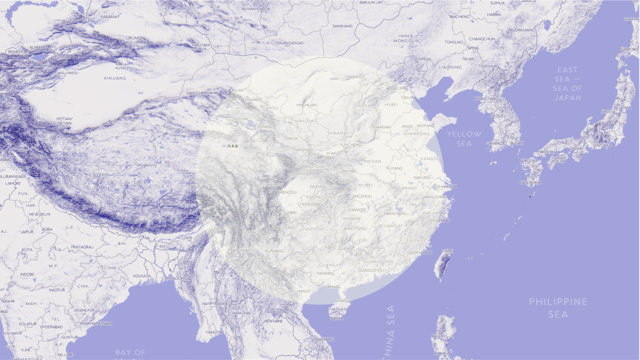

The history of China’s policy towards its Uighur Muslim minority has always been fraught with tension. The Chinese government considers China a multi-ethnic state consisting primarily of the Han Chinese and has historically implemented policies of assimilation in order to ensure the progress and uniformity of the communist state. China’s Sinicization efforts have led to Uighur unrest and bloody violence, as characterized by the 2009 Urumqi riots which occurred in reaction to two Uighurs being killed at a toy factory in Shaoguan.

In more recent years, the calculated campaign against the minorities has been spearheaded by Chen Quanguo, the Communist Party Secretary of Xinjiang Province and a nationalist hard-liner. As outlined in the leak made to the ICIJ, deputy-secretary Zhu Hailun also plays a key role in the planning and execution of the campaign against the Uighurs. Exact numbers are unclear, however multiple sources have estimated that as of 2018, there are up to one million Uighurs, Kazakhs, Kyrgyz and other ethnic Turkic Muslims imprisoned in the detention centers designed by the Communist Party. It was also revealed that the Party uses a manual that instructs prison staff on how to recruit Xianjiang residents for detention, how to prevent escapes, methods of forced indoctrination and how to maintain secrecy about the camps’ existence. Although officially the individuals are held there for “retraining” against religious extremism and given lessons in Mandarin and Communist Party ideology, it is evident that this is a calculated campaign of cultural genocide. This is further confirmed by members of the Uighur minority who have managed to escape the camps, and have detailed horrific tales of torture, interrogations and forced confinement.

A polarized reaction

The reaction of the international community has been divided. On 29 October 2019, UN Ambassador Karen Pierce delivered a joint statement urging an end to the repression of Turkic Muslims at the General Assembly’s Third Committee. 23 countries backed this statement, including France, Germany, Japan and the United Kingdom. However, a greater number of countries chose instead to stand behind Xi Jinping, illustrating the stark disparities of opinion within the international community when it comes to condemning China’s human rights abuses. 54 countries, including Russia and members of the Organization for Islamic Cooperation, praised the Chinese government’s management of Xinjiang. Further, Belarussian Ambassador Valentin Rybakov addressed the UN Human Rights Committee by saying: “Now, safety and security have returned to Xinjiang and fundamental human rights of people of all ethnic groups there are safeguarded. We commend China’s remarkable achievements in the field of human rights”.

This can be explained by the Gulf State’s reliance on China for military, economic and religious reasons. In particular, the Organization for Islamic Cooperation (OIC) backs China due to their 2018 economic partnership consisting of construction and investment contracts worth 28 billion USD as part of its Belt and Road Initiative. As the Middle East already struggles to attract foreign investment, these Muslim-majority countries are not necessarily defenders of their faith when economic development is at stake. Semi-autocratic states such as Russia and Venezuela also back China due to their general opposition to what they consider to be a Western global human rights regime. Within the context of the UN, it is clear that China exerts considerable power, which will only continue to allow the administration to veil their human rights abuses.

Who can hold China accountable?

Divisions within the UN and the international community have resulted in weak and ineffective condemnations of China’s human rights abuses. The U.S. has been leading the sanction movement against China and in 2019, blacklisted 28 Chinese companies, government offices and security bureaus in order to ensure that Chinese companies are unable to import American products and technology. Further, the Uighur Act of 2019 is in the midst of being passed in the U.S. House of Representatives. It calls on President Trump to impose sanctions against senior Chinese officials, even as he seeks a trade deal with Beijing. More states must follow the U.S.’ lead and assert a stronger stance against China. However, China largely benefits from the rules-based international economic order, meaning that many countries are unwilling to risk the loss of lucrative trade deals with Beijing in favour of promoting human rights.

Further, the normal avenues for recourse under international law are largely unavailable due to China’s veto power within the United Nations Security Council. Utilizing the International Criminal Court’s compliance mechanisms present in the Geneva Conventions could be an opportunity to galvanize the international community into ending Chinese impunity and holding them accountable to the rule of international law. In conjunction with the work of civil society organizations such as Amnesty International and the International Federation for Human Rights, surely China cannot continue to veil its mass incarceration under the guise of re-education attempts. Combined with the mounting pressure from journalists to gain unfettered access to the detention camps, one can hope that enforcing compliance through international law can expedite formal investigation proceedings in the future.

About the author:

Rachel Coburn is a second-year Master’s student in International Studies at Aarhus University, with a background in Political Science and History. She chose to complete an internship at the Institute of International Relations Prague in Fall 2019 to pursue her interests in foreign policy within Eastern Europe and East Asia, particularly in the field of transnational crime and human rights.